Attention, Pressure and The Compounding Effect of Errors

What Attention Control Theory - Sport can tell us about performing under pressure

Have you ever been performing under pressure and made an error? Maybe it was an important match or a big competition. Sometimes in these situations even when you know that the cost of an error is high and you try to avoid them, one error seems to lead into another, and a downward spiral can begin. In this post I’m going to discuss Attentional Control Theory: Sport (ACT:S) (Eysenck & Wilson, 2016), which describes how anxiety can impact attentional control during sport performance and offers explanations for the compounding effect of errors. This post will hopefully help you to understand this model, make sense of some of these situations and, crucially, provide tips to counteract the negative effects of anxiety on performance.

Researchers have devoted considerable time and effort to trying to understand the mechanisms of performance breakdown under pressure. Typically, this has focused on the concept of choking. A choke can be considered an enormous breakdown in performance, relative to the athletes expected level, under pressure. I’m sure readers can all think of examples, with Bill Buckner and Greg Norman some of the most famous. Research has largely been split between self-focus theories and distraction theories.

Self-focus theories suggest that under increased pressure athletes attempt to exert conscious control over well-learned movements and this leads to performance breakdown. These well-learned movement patterns are better suited to firing without our conscious input. Think for example about tying your shoes, this is a well-learned skill that I’m confident you can perform, without any sort of conscious thought to what you’re doing. Now, imagine you were asked to think about all the fine motor skills involved and try to control the specific movements of your fingers whilst you’re doing the movements. I would be willing to bet that this somewhat disrupts the flow of your shoe-tying.

Distraction theories on the other hand, generally contest that performance breakdown results from anxiety, making athletes too distractable and unable to maintain focus on task-relevant information. We can imagine a footballer about to take a penalty and due to the anxiety and nerves, fails to account for the movement cues the goalkeeper may be providing.

In their simplest forms, its often said that self-focus choking is due to focusing too much on the task at hand and distraction choking is not focusing enough on the task.

There is lots of supporting evidence for both theories in both quantitative and qualitative studies and with some research arguing both self-focus and distraction lead to choking. Within both schools there are also several different theories that explain the mechanisms at play. It is not the intention of this post to describe all these theories but rather, to briefly introduce some central ideas before giving an overview of ACT-S.

To achieve this, we’re going to have to begin by moving two theories back to provide a brief description of Processing Efficiency Theory. However, if you feel like that extra context isn’t for you, and you just want to get to the main focus of this piece, feel free to skip down to the ACT:S section below.

Given that both self-focus and distraction theories are based on how attention is allocated, it is important to understand the concept of attentional control. Attentional control can be considered the ability to choose what to pay attention to, what to ignore etc and is thought to be very important in performance of a variety of tasks. Or, in more depth

“Attention control allows us to pursue our goals despite distractions and temptations, to deviate from the habitual, and to keep information in mind amid a maelstrom of divergent thought” (Engle, 2018).

More specifically, attention control refers to the general ability to regulate information processing in service of goal-directed behavior. It is also referred to as cognitive control (Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2001), executive control (Baddeley, 1996), and executive attention (Engle, 2002), and it shares many similarities with the executive-functions framework of Friedman and Miyake (2017). Simply put, attention control is a common thread linking performance on many complex cognitive tasks, particularly those requiring active goal maintenance and conflict resolution (Burgoyne et al., (2020))

Processing Efficiency Theory

The first theory on anxiety and performance we’ll look at in this post is PET. PET is mainly concerned with the role of worry and working memory when considering how anxiety impacts performance. Within PET, worry is the thinking component of anxiety (Brimmell, 2022). You might think of this as the voice in your head that presents all the fears, self-evaluation etc., that may come up during performance. Within PET, worry is quite taxing for the performer and can exert two different influences on performers:

1) Worry takes away bandwidth (storage/processing resources) that would be better served for performance. This can have a negative impact on performance, especially those tasks requiring brain power. PET contends that anxiety influences performance primarily through impact on working memory, in particular the central executive system, the main component of this system.

2) Worry can have a motivational function and can influence the deployment of cognitive resources. For example, an athlete can worry about how performance is going based on error feedback and self-regulate by deploying more resources in the form of more effort. This may negate the negative impacts of worry on performance and maintain performance levels of performers.

A crucial aspect of PET is the differentiation between performance effectiveness and performance efficiency. Performance effectiveness is concerned with the end result (i.e – did the performer execute what they wanted to) whereas performance efficiency factors in both effectiveness and the resources required to achieve that result (i.e – you may still execute your aim but the performer was required to input considerably more effort to maintain focus and execute).

In terms of limitations it is argued that the PET fails to specify which functions of the central executive system are affected by anxiety and PET does not consider circumstances where an anxious performer can outperform non-anxious performers.

Attentional Control Theory

Building on many of the suggestions from PET, Attentional Control Theory (Eysenck et al., 2007) also addresses some of the limitations. There are two main additions to observe within ACT:

1) The addition of two neurological attentional systems (the goal-directed and the stimulus-driven systems). The goal-directed system can be considered a top-down system concerned with using attentional resources for meeting goals and finding task-relevant stimuli. The stimulus-driven system is more reactive, more bottom-up, devoted to noticing unexpected, threatening and salient stimuli. ACT proposes that under anxiety the balance between these systems is disrupted such that the influence of the stimulus-driven system increases i.e – performers become more distracted by threatening, non-task relevant stimuli – perhaps the crowd etc.

2) ACT adds detail on the specific aspects of attention control and the functions of the central executive system that are affected by anxiety. Research has suggested that there are three linked, but distinct functions performed by the central executive: inhibition, shifting and updating. Inhibition is the capacity to withhold responses and avoid distraction, whilst shifting is the capacity to move back and forth between tasks and focus of attention. Updating is concerned more with storage and replacing outdated information with newer, relevant information. ACT proposes that the imbalance between the attentional systems in point 1 is caused by anxiety negatively impacting performers inhibition and shifting capabilities. For example, inhibition function can prevent distraction from task-irrelevant stimuli (e.g - arguments with opponents) whilst the shifting function allows attention to be flexibly directed toward task-relevant cues (e.g. goalkeepers position, are you onside etc). Disruptions to these systems can lead to increased influence of the stimuli-driven system.

ACT assumes that it is performance efficiency is impacted most by anxiety, rather than performance effectiveness and again, ACT assumes that by deploying further resources, it is possible for performers to maintain their levels in the face of anxiety. However, it should be noted that ACT expects the negative effects on performance to increase as anxiety increases. This inefficiency can be traced to anxiety’s influence on the shifting and inhibition aspects of attentional control. Eye tracking research has provided some support the suggestions from ACT whereby athletes with higher anxiety displayed less efficient eye tracking behaviour with higher search rates and shorter quiet eye durations. Despite this, a more sport specific ACT model was developed.

Attentional Control Theory-Sport

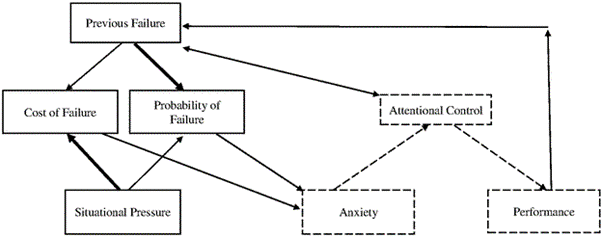

*A figure illustrating the ACT-S model and how each component relates*

As you can probably tell by the increase in arrows and boxes between this diagram and the last, ACT-S features expansions from ACT. However, several aspects remain consistent; the relationship between anxiety, attentional control and performance, compensatory factors like motivation and effort can again play a role in limiting the potential negative impacts of anxiety on performance, and anxiety is likely to impact performance efficiency, more so than performance effectiveness.

The Sport model however, increases focus on what leads to this anxiety, the antecedents. Drawing on a two-phase model of worry from Berenbaum (2010;2007), ACT-S suggests that anxiety is brought on by appraisals of 1) the perceived cost of failure and 2) the perceived likelihood of failure. An important point to include here concerns the nature of situational pressure (i.e. rewards, social comparison, consequences) – the anxiety will only be experienced by the performer if they believe 1) it is meaningful or 2) it is likely to occur.

ACT-S therefore identifies the nature of compounding errors and the effects that this may have. Within ACT-S the probability of failure increases as the number of error experiences increases. This increased likelihood of failure then ramps up the intensity of anxiety and the subsequent negative impact on performance in a repeating pattern. When combined with a situation whereby the cost of failure is high, it is thought that there is an interactive effect, i.e in a situation where pressure is high and the cost of failure is high, an athlete is perhaps more likely to view errors more negatively.

Examples from the Research

Two studies using archival data from both team and individual sports have produced supporting evidence for ACT:S model. Both conducted by Harris et al., these studies investigated situational pressure and compounding errors in NFL (2019) and tennis (2021). In both studies, situational pressure was assessed using a 6-point scale designed by the authors (0 - low pressure, 5 - High pressure).

Taking the NFL example first, the scoring system operated on a cumulative basis whereby a point was added if: i) it was the 3rd or 4th down, ii) the scoreline was close iii) it was close to the end of the game (final quarter) iv)the team with the ball was losing v)the play began within 20 yards of end-line. Performance failure was defined as losing the ball (interceptions, sacks, fumbles) or failing to make ground (receiver tackled behind line of scrimmage). Post-failure plays were plays that immediately followed a performance failure in the same drive. 212,356 running and passing plays were analysed and coded from 2009-2016. The regression model *statistical jargon incoming* “indicated that increasing pressure score was a reliable predictor of performance failure”, furthermore authors reported that “failure on the preceding play increased the chance of a further failure by 1.09 times” with an interaction between prior failures and the pressure score such that increasing the pressure score by 1 point was 1.1 times greater in the effect on performance when the previous play was a play failure.

Now, what does all that jargon mean?

In simple terms, as pressure went up plays were more likely to result in failure and plays were more likely to result in failure if the previous play was also a failure. The strongest effects were when pressure was at it’s highest and the previous play had resulted in an error. These findings suggest the compounding effect of errors and the impact of pressure on performance. The size of the dataset used from real-life, elite competitive sport makes a compelling argument. However, I’m sure readers are thinking it may be unfair to consider performance failure in these team-invasion situations where so many actors are involved and errors are hard to assess compared to good play by the opponent.

Aiming to assess the model in an individual sport setting, Harris et al., (2021) subsequently tested these ideas with a dataset from elite tennis where 658,068 points across 12 Grand Slam tournaments between 2016-2019 were analysed in a similar fashion to the NFL plays. Double-faults or unforced errors were coded as errors in this dataset. Similar to the pressure situations of NFL plays, a pressure scoring system was devised where factors such as break-points, game-points, if the game was in a deciding set, if opponent had break point or game-point were coded as a point on the scale.

As observed in the NFL study, the mixed effects logistic regression model again illustrated that increase on the pressure scale significantly increased the likelihood of an error. An error in the preceding play also significantly increased the likelihood of an error on a given play. A multiplicative effect was also suggested with the negative effect of previous errors at the strongest when the situational pressure was high. These findings, when paired with those of the NFL study emphasise the impact that prior errors and pressure can have on performance.

However, these studies are not without limitations. The conceptualisation of pressure in these studies is one such issue that readers should factor in. As we addressed earlier in this post and in others, a key part of the pressure equation is the athlete’s perception of pressure. The objective factors like game-state and consequences associated with the situation are useful indicators of pressure but we cannot guarantee that the athletes are experiencing pressure in these situations. If, pressure is characterised as an increased sense of importance for performance – it is difficult, if not impossible, for any study to confidently determine an athlete is perceiving this. However, whilst acknowledging this limitation, and taking on board the key aspects of ACT-S, lets picture at how this might pay out in real-time.

Consider the following example

A golfer is one-up in the final of the club match-play tournament with 3 holes to play. They had started the back 9 three-up but they’ve hit a few errant shots, and their opponent has won two of the last 5 holes. On 16, they hit a nice tee-shot but have now hit a poor approach shot into the green-side rough. As they approach their next shot, a tricky chip over a bunker with not much green to work with, the previous errors lead our athlete to perceive an increased probability of further failure. This increase in perceived likelihood causes the golfer to experience anxiety or worry. Thoughts swirl in their head, which negatively impacts their attentional control. The stimulus driven system kicks into overdrive, triggering the golfer to direct attention to the ‘threat’ presented by the crowd of onlookers and the potential embarrassment of throwing away a 3-hole lead. The golfers find it difficult to shift focus toward the task-relevant stimuli – i.e what shot is most appropriate for this situation, where do I want my ball to land, can I get any spin on the ball etc. Consequently, they fail to notice the ball is sitting in an old divot. Our performer catches the next chip just a fraction thin sending it into the bunker, thus strengthening the feedback loop from previous errors.

Reading this example, I think it’s possible to place ourselves in the golfers shoes. We can understand how these thoughts, feelings and events interact to produce the end result. Perhaps you can think of examples from your own sporting career or from athletes you coach and how similar patterns have emerged. So bearing all this in mind, what can an athlete do to prevent the negative effects of pressure and previous errors?

Taking Action

As there are different stages within ACT-S model, there are perhaps different stages at which interventions and approaches can be targeted. Three potential options are briefly explained below

1) Routines – Both pre-and post-performance routines are helpful ways for athletes to maintain focus. Pre-performance routines may help keep athletes in the moment and prevent thoughts drifting toward both the costs and probabilities of failure. If the perceived cost and probability of failure remain low, the pressure intensity athletes experience will likely be lower. These routines could also feature elements like specific areas of focus to ensure task-relevant information is gathered thus addressing the attention aspect of the model. Post-performance routines can help athletes to leave errors in the moment they occur. Making this a habit may help athletes to change their perception of errors in line with a more mindful, acceptance-based approach. If errors are not viewed as negatively, it may limit their potential to increase the probability of failure component of the model.

2) Goldfish – whilst it sounds very simplistic and the reality of implementing this strategy may be more difficult in practice, forgetting mistakes is one effective way to limit the negative effects of errors.

– As Ted Lasso is aware, a goldfish is famed for having the shortest memory of any animal. The ability to forget your mistakes and move on may act as a circuit breaker in the chain toward a perception of increased failure probability. Two-time Major winning golfer Dustin Johnson was famed for his ability to forget his bad shots. Whilst that’s not always easy, Dr. Bob Rotella suggests that a good place to start is to stop re-living them. When we catch ourselves replaying images of mistakes and errors, stop, pause and try to think of something else. It doesn’t have to be images of success but not picturing the errors is certainly a step in the right direction.

3) Pressure training – this is more focused on the preparation aspect rather than during the performance, but due to the interaction between these factors it’s possible that by limiting the effect of pressure, athletes may lower the number of errors. Check out my previous post on what is pressure training to get a better idea of how athletes can use this methodology to build tolerance to pressure and limit the negative effects.

What is Pressure Training?

As Euro2024 approaches the knockout stages and the threat of penalty shoot-outs looms on the horizon, the conversation will inevitably turn to how teams can best prepare for this eventuality. Gone are the days of the “It’s a lottery” cliché and the belief that “anything can happen on the day”. In the era of analysis, statistics and preparation, teams ar…

In conclusion, this post has begun by introducing choking, and the two main schools of thought around how it occurs. We’ve looked at the concept of attentional control before diving into an overview of Processing Efficiency Theory and Attentional Control Theory. We’ve looked at the main aspects of these theories and then moved onto the sport specific ACT model and how it has built on those previous models. We looked at two archival studies from elite sport competitions that provide support for the ACT-S view of pressure, errors and attention before closing with three suggestions for how athletes and coaches can help athletes to perform under pressure. If you have any comments or feedback on this piece – please do share some below. If you’re interested in Sport Psychology services for yourself or your team, check our my website: https://gbyrnecoaching.wixsite.com/my-site

Berenbaum, H., Thompson, R. J., & Bredemeier, K. (2007). Perceived threat: Exploring its association with worry and its hypothesized antecedents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(10), 2473-2482.

Berenbaum, H. (2010). An initiation–termination two-phase model of worrying. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 962-975.

Brimmell, Jack (2022) The Role of Attentional Control in Sport Performance. Doctoral thesis, York St John University.

Burgoyne, A. P., & Engle, R. W. (2020). Attention Control: A Cornerstone of Higher-Order Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(6), 624-630. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420969371

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336.

Harris, D. J., Vine, S. J., Eysenck, M. W., & Wilson, M. R. (2019). To err again is human: Exploring a bidirectional relationship between pressure and performance failure feedback. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(6), 670-678.

Harris, D. J., Vine, S. J., Eysenck, M. W., & Wilson, M. R. (2021). Psychological pressure and compounded errors during elite-level tennis. Psychology of sport and exercise, 56, 101987.

Harris, D. J., Arthur, T., Vine, S. J., Rahman, H. R. A., Liu, J., Han, F., & Wilson, M. R. (2023). The effect of performance pressure and error-feedback on anxiety and performance in an interceptive task. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1182269.